Tax Litigation

The Way to Challenge a Bad Audit Outcome

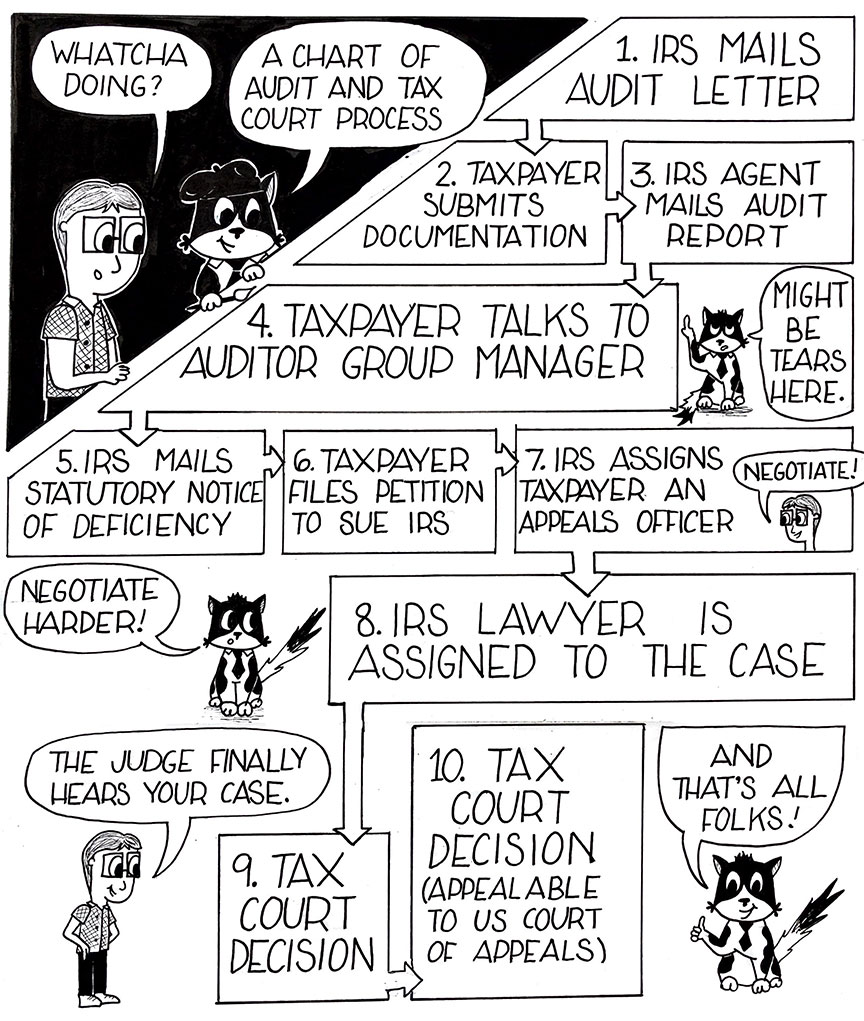

So, you or your business were audited. You received the IRS Audit Report outlining what the IRS disagreed with your tax return(s) and telling you what changes they’re making. You owe more in tax and now there’s interest, too. You probably didn’t have sufficient documentation to back up some deductions. Nonetheless, you disagree with the auditor’s decision. A few weeks to a few months later, the IRS sent a Statutory Notice of Deficiency and asked you to either sign a waiver saying you agree with their changes and your new bill, or file a petition with the US Tax Court. This is normally the time clients hire me. The audit process up until now is relatively straightforward and usually doesn’t require specialized legal knowledge. However, once the IRS issues the Statutory Notice of Deficiency, the process of challenging the IRS becomes less straightforward and knowledge of the bureaucracy becomes very helpful.

The best time to speak to an attorney is when you get a notice of deficiency – that’s when specialized IRS knowledge makes a difference

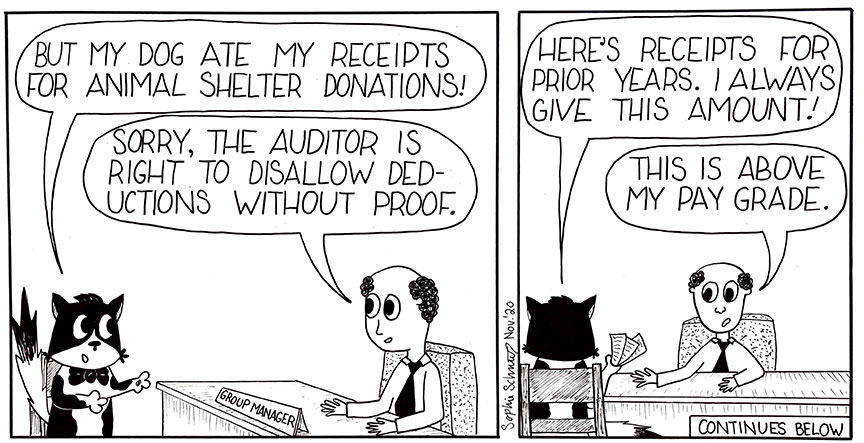

Attempting to Get Audit Result You Want with the Auditor’s Group Manager

It’s almost always worth it to pursue good-faith disagreements with the IRS. Why? Because the taxpayer who disagrees with their Audit Report or Statutory Notice of Deficiency will enter a process where they are dealing with IRS representatives who have increasing amounts of discretion. This is critical to negotiating the results of your audit. Why? The auditor is at the bottom of the IRS hierarchy; s/he has the least amount of discretion in adjusting audit results. Auditors are judged on following tax law and procedures precisely. Recall that the IRS is mandated by Congress to apply tax law and policy equally to all taxpayers: your auditor is the front-line of this mandate. They must collect proof for deductions on tax returns that were flagged for audit – equally from all taxpayers they audit. Your auditor cannot allow deductions without documentation, or with documentation that is unfamiliar. If your documentation is atypical and the auditor is unfamiliar with it, then s/he will not allow it because s/he knows the matter is likely to go up further in the bureaucracy, to a Group Manager, or an Appeals Officer, or an IRS attorney, or ultimately a Tax Court judge, who will know whether the atypical documentation can be accepted.

Enter your auditor’s manager. Each auditor has a Group Manager (who manages 3-10 junior auditors), someone usually promoted from within because s/he was a good auditor. This Group Manager has more discretion than the auditor on your case. Most Group Managers will meet with a taxpayer who politely and firmly articulates their disagreement with the auditor’s findings and requests a meeting with the manager to discuss differences. Depending on the complexity of the issue, the Group Manager may or may not feel comfortable overriding the auditor. If the Group Manager does allow the disputed item, that’s great news. You’ve gotten the desired outcome quickly and without much effort. If the Group Manager doesn’t override the auditor’s decision and continues to disallow an expense (either because s/he believes the auditor is correct or because s/he also doesn’t know the correct way to resolve the issue but knows people above her in the bureaucracy will have an answer), then you’re on to the Litigation Stage.

Petition to sue the IRS, don’t file a formal appeal

Filing an Appeal – Don’t!

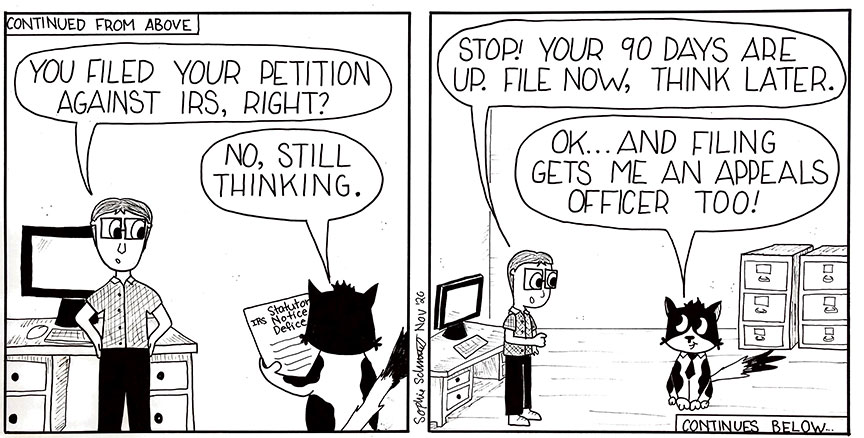

Let’s assume speaking with your auditor’s Group Manager also didn’t get you an audit result you’re happy with, which is the most likely outcome. You may now file an appeal with the IRS Office of Appeals, but you shouldn’t (here’s the link)! Why? Isn’t an appeal a reasonable step to try before all-out litigation? No! You want to force the IRS to issue a Statutory Notice of Deficiency. There are several reasons for this. First, you cannot file a petition before the Form 4549 Statutory Notice of Deficiency has been completed and sent to you (though this can take from two weeks to six months after your Audit Report is issued). And you want the Statutory Notice of Deficiency to be filed because this official government position on your audit “freezes” the IRS from raising any additional issues, such as expanding the expenses under examination.

Second, once you have filed a petition in Tax Court against the IRS, you will automatically be assigned an Appeals Officer anyhow. The IRS tries to resolve disagreements between the IRS and the taxpayer long before an actual trial, as do most courts. If your case is docketed in Tax Court, then the Appeals Officer assigns it a higher priority.

Third, you have only 90 days from receipt of the Statutory Notice of Deficiency to file your petition against the IRS, so you’d be highly unlikely to achieve a resolution with the Appeals Office before needing to file the petition, since it normally takes several months for an Appeal Officer to be assigned to your appeal.

Fourth, if you request an Appeal before filing a petition against the IRS, then the IRS can extend the time it has to legally impose more tax. That clock typically expires after three years (read more about it here, scroll to the Audit Timetable: Three-Year Assessment Rule Section), but when granting Appeals, the IRS requires the taxpayer to sign a document saying they agree the IRS can add a year or two to that normally 3-year statute of limitation.

Always skip an appeal and go straight to filing a petition to sue the IRS

Filing a Petition to Sue the IRS in U.S. Tax Court

A lawsuit against the IRS must be filed within 90 days of the issuance of the Statutory Notice of Deficiency, or the Tax Court won’t hear the case (here’s their website). The instructions for filing a petition will be included with the Statutory Notice of Deficiency. “Filed” means put in the mail or delivery service (Fed Ex, USPS) by midnight of the 90th day after you received the Notice of Deficiency. The case law on this timely mailing rule boils down to this: unless the taxpayer can show a date-stamp asserting that s/he mailed the petition before midnight of the 90th day, s/he loses. To avoid problems, it’s best to mail your petition disputing the IRS’s determination by registered or certified mail. If you miss the 90-day deadline to file a petition, there’s still one recourse available. Since it can be daunting to sue the IRS, most of my tax clients find me at this stage in the audit process.

Small versus Regular Tax Court Cases

If less than $50,000 in deficiency (not including penalties and interest) is at issue, the taxpayer may choose to file his Tax Court case as a small case or a regular case. A small case cannot be appealed but there are two advantages to small case filings. First, a small case is likely to be heard more quickly because the Tax Court holds more small-case calendars than regular case calendars. Second, since a small case cannot be appealed or used as precedent, the judge may bend the law in the taxpayer’s favor. As an example, while at the IRS, I had a small-procedures case against a nurse who deducted the cost of her clothes – not her scrubs – used at work (among other deductions). The Tax Code is pretty clear that any work uniform cannot be worn on the street in order to be deductible. The judge heard the nurse’s story and found the nurse credible and sympathetic, so he gave her the unwarranted deduction. In regular cases, the judge is more likely to follow both the Tax Code and the Rules of Evidence because either the taxpayer or the IRS may appeal the decision, so process must be followed scrupulously.

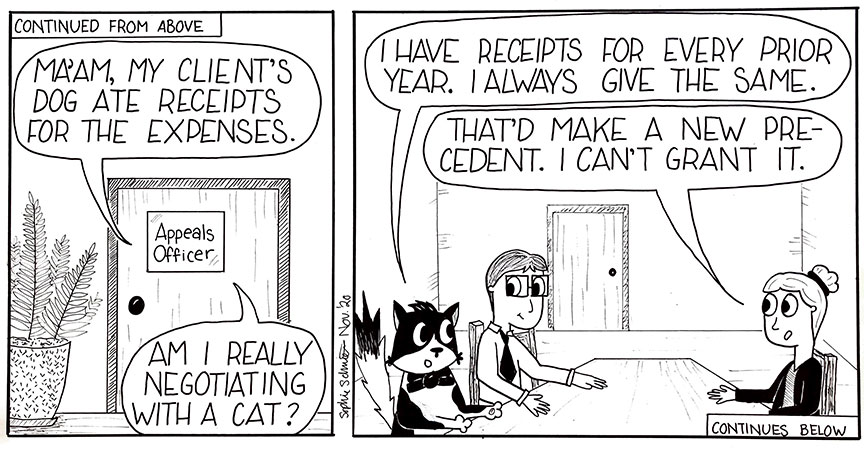

Appeals Officer

Once a taxpayer files a petition against the IRS in Tax Court, the IRS assigns the case to an Appeals Officer. This is a second IRS employee (after the auditor’s Group Manager) the taxpayer can negotiate with. Importantly, as a taxpayer deals with successively-higher-level employees in the IRS, their discretion increases. Appeals officers almost always have more discretion in the kind of allowances they can make to settle a case than auditors do. The next step up in authority over an appeals officer is typically the IRS trial attorney, who defends the IRS’ position if the Appeals Officer and the taxpayer cannot come to an agreement.

The IRS has set up the appeals process to be as fair as possible to taxpayers, and to save itself the cost of litigation when possible. After all, even the most conscientious auditors make mistakes. Once the auditor issues a final Audit Report, detailing any changes to the deductions, income and taxes owed in the tax return being audited, the taxpayer can ask that the report (or elements therein) be reconsidered. The Appeals Officer performing this reconsideration is an IRS civil service employee who has auditing experience, but who has not been previously involved in the particular case. Appeals Officers have quasi-judicial power to settle disputed audits. They are not allowed to contact the auditor on the case but rather receive the document file of the taxpayer to review, meet with the taxpayer as necessary to understand the nature of the objections to the auditor’s determination, and adjust those determinations as they think is appropriate.

Taxpayers can ask for a review of any auditor decision

IRS auditors and lawyers love their Appeals Officers. Appeals Officers often make the determinations of the IRS more transparent to the taxpayer, thus enhancing the IRS’s legitimacy. They also settle the vast majority of cases set for trial, thus saving the IRS substantial resources. Finally, the IRS does not like public losses, and Appeals Officers help to filter out the weaker/losing tax cases before they reach the courtroom. I prefer negotiating with Appeals Officers because they have discretion to settle cases and are generally more amenable to finding a mutually acceptable solution than are auditors. Bottom line: if you really don’t like the outcome of an audit, don’t be afraid to file a petition to sue the IRS. You are highly unlikely to end up in court, but you will get an Appeals Officer with whom you can often come out ahead. If that seems too intimidating, call me and I’ll step in for you.

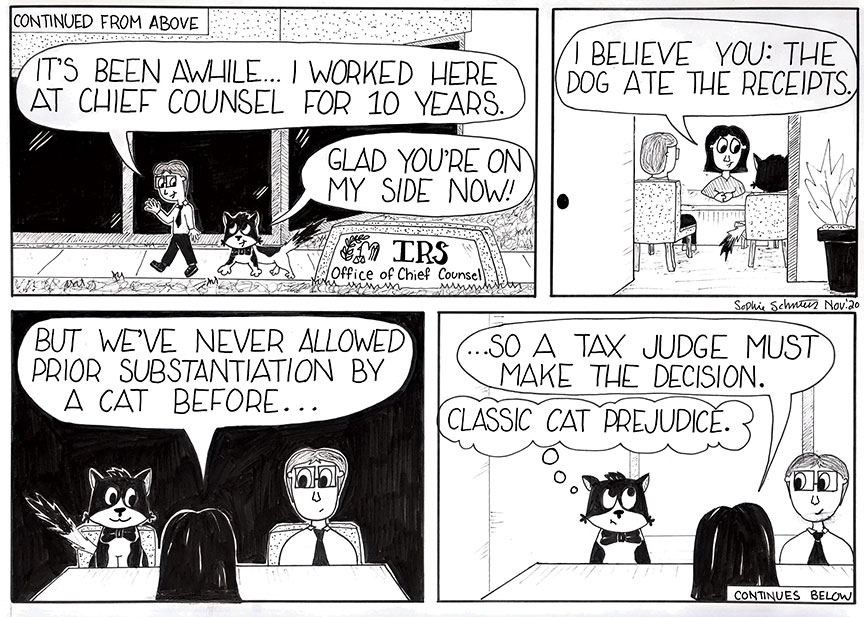

Office of Chief Counsel of the IRS

Filing a Tax Court petition actually first puts the audit disagreement in front of the Office of Chief Counsel of the IRS. These IRS attorneys have even more discretion than Appeals Officers to settle cases. The attorney assigned to your case will always send it to an Appeals Officer for resolution first, before putting any real work into it. If the dispute cannot be resolved with an Appeals Officer, then the Chief Counsel attorney attempts to do so. Indeed, Tax Court rules require that the taxpayer and IRS attorney meet, confer, and prepare a lengthy stipulation outlining the facts on which they agree and disagree prior to the case’s trial. The Tax Court pushes the IRS and the taxpayer together in this manner because it tends to lead to settlement. As with most types of litigation, far more tax cases enter the pipeline than are actually tried: as a Chief Counsel attorney, I had primary responsibility for at least 1,500 cases but only eighteen went to trial. The rest were settled: either the taxpayer gave up, the IRS conceded or, most frequently, there both sides conceded on some issues. Most years only one percent of the tax petitions filed actually are heard in U.S. Tax Court.

Tax Court and Trial

If the case cannot be resolved with the Chief Counsel attorney, then it proceeds to trial, which puts the taxpayer in front of a Tax Court Judge who has the most discretion of all. Tax Court judges are appointed by the President under Article I of the Constitution and serve 15-year terms. The Tax Court sits in Washington, DC, but its judges “ride circuit,” that is, they hear cases all over the country. Large cities such as Los Angeles get 10-15 visits from Tax Court judges per year, each visit for one to two weeks. Smaller cities (Fargo, ND, for instance) will get one two-day visit a year. Tax court judges are typically former tax attorneys at private firms; fewer judges come from IRS or Department of Justice backgrounds. They are experts in tax law.

It is impossible to generalize about the actual trial process in Tax Court. As with all other trials, the nature and complexity of a particular issue determines how long trial will last and all other particulars. Federal Rules of Evidence and specialized procedural rules apply in a Tax Court case. Yet the procedures in Tax Court are sufficiently informal that an individual taxpayer who is not an attorney could conduct a case against the IRS. This is because the Tax Court judges seek to let the taxpayers tell their story and thus give them great latitude. The atmosphere in Tax Court is more formal than a traffic court, but less formal than many other courts. If you need to go before the Tax Court, you may not need an attorney to prevail, though most taxpayers do hire one. In any case, call me so I can either advise you on how to present your case, or on why you should have an experienced litigator take over.

After trial, the judge will ask for the two sides to submit briefs. Depending on the issues in the case, the IRS attorney may need to send her brief to the National Office for review, as happens typically with complex issues or ones with little precedent. After receiving briefs, the judge takes the case “under advisement” and issues a written decision generally in about a year, but sometimes not for several years. The taxpayer does not need to pay the tax before filing the case but, until a decision comes down from the judge, penalties and interest accrue on the final tax. Once you have agreed to an amount you owe, or the Tax Court decides how much you owe, the IRS assesses the tax. The decision is final, and the IRS gets to start its collection process. Learn about Collections here.

Appealing the Tax Court’s Decision

Either the IRS or the taxpayer may appeal the Tax Court’s decision. The appeal goes to a federal Court of Appeals for the circuit where the taxpayer lives (in California, the 9th Circuit). Appeals can only allege that the judge applied the law wrongly; the appeals court does not want to hear the facts again and assumes that the trial judge knew the facts better than the circuit court ever will. Recall that small cases cannot be appealed.

Successful appeals of Tax Court decisions are rare

Refund Litigation in U.S. District Court

If a taxpayer fails to file a timely petition in Tax Court and thus loses the chance to sue the IRS there, then the taxpayer still has a chance to challenge the amount owed. S/he can pay the tax and then make a claim for refund (see the form here). The IRS has six-months to refund the overpaid tax or reject the claim. Once the IRS rejects the claim, then the taxpayer may bring suit in either the Court of Federal Claims or the local United States District Court. These forums are much more formal than the Tax Court. Hiring a lawyer is highly recommended to pursue a refund suit. A taxpayer may request a jury trial in District Court. In my experience, it’s more difficult to convince a District judge to be lenient on a tax matter than a Tax Court judge.