Offer-in-Compromise

The Offer-in-Compromise (“OIC”) process is invasive, lengthy, and only rarely successful. There’s a popular perception that many people get large amounts of tax debt reduced by filing for one. They don’t. Very few Offers-in-Compromise are accepted by the IRS. On average, the has IRS accepted only about 40 percent of OICs.

Why Are So Few Offer-in-Compromises Accepted by the IRS?

The congressional committees that oversee the Treasury Department (the agency that houses the IRS) have mandated that the IRS collect the full amount of taxes owed from everyone who owes. After all, it’s only fair. That means that the few Offer-in-Compromises the IRS does accept are largely for very elderly people or people who have permanently lost the ability to earn an income. With everyone else, the IRS holds out for the possibility the taxpayer will be able to repay in the future. Just because a taxpayer is unemployed today, doesn’t mean they won’t work in the future and earn everything needed to repay the taxes owed. My clients often think the IRS would be better off collecting what it can today, rather than holding out for the possibility of collecting everything in the future. For instance, if I owe $10,000 but can only afford $1,000, why not take what you can get today, let me off the hook for the rest, and not spend time and money trying to collect from me in the future? That approach assumes the IRS is primarily a collections agency. It’s not. It’s primarily a law enforcement agency and it has been ordered by Congress to apply the tax laws and collection efforts equally. The IRS cannot cut “special deals” except when there’s irrefutable evidence that a taxpayer will never be able to repay fully in the future. Indeed, it actually took an act of Congress – I.R.C. § 7122 – to give the IRS the authority to write off a tax debt with the Offer-in-Compromise.

What’s the Process for Applying for An Offer-in-Compromise?

There are actually three types of OICs. The first is OIC for Doubt as to Liability but only a handful of these are filed because almost all challenges by the taxpayer as to the tax owed is completed with an audit reconsideration or an audit appeals – in other words, long before the taxpayer’s file has gone from the IRS Assessment division to the IRS Collections division. The second type of OIC is for Effective Tax Administration in which the tax owed is forgiven for public policy considerations so obscure that only a handful of OICs have been filed in the past decade under this heading. The third kind of OIC is Doubt as to Collectibility and constitutes over 95 percent of OICs. In 2019, almost 100,000 were filed. The rest of this discussion focuses exclusively on the Doubt as to Collectibility OICs.

The process to qualify for an OIC looks a lot like bankruptcy, only the IRS is the only creditor. The taxpayer provides an accounting of everything he owes and owns, and his income and expenses. Here’s the form that needs to be submitted to be considered. The OIC qualification is based on a computation of the taxpayer’s ability to pay his or her tax debt before the IRS runs out of time to collect the debt (called the collection statute expiration date, which almost always is ten years from the date the final tax amount due was set by the IRS). The IRS decision is largely based on computational formulas which is why it offers taxpayers a pre-qualifier tool. To qualify for an OIC, you must prove that you can’t pay the total tax owed before the collection statute expires (usually ten years), using the net equity in your assets plus any future income.

How are Basic Living Expenses for An Offer-in-Compromise Calculated?

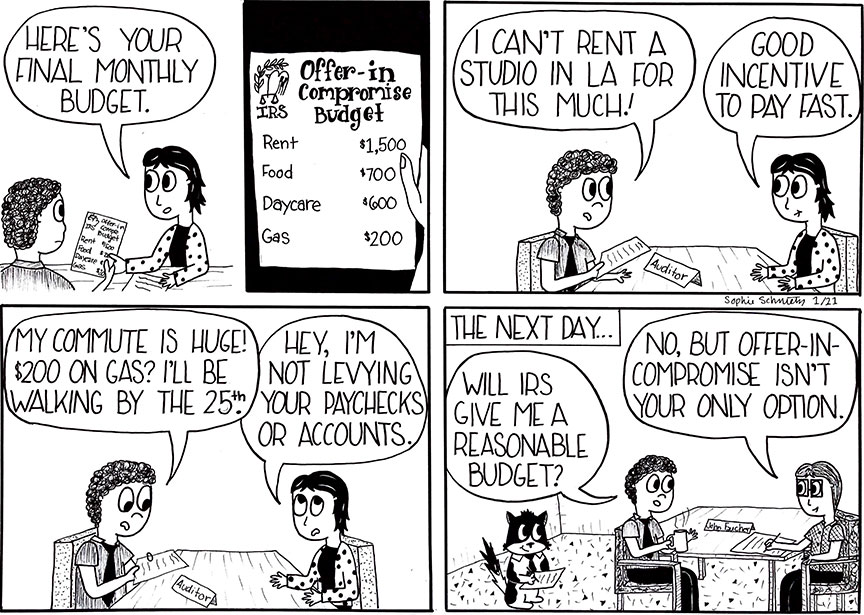

The IRS calculates future income as the amount it can collect on a monthly basis (monthly disposable income minus basic living expenses) before the collection statute expires. The living expenses allowed are very limited – no payments for season’s football tickets, or charitable contributions, or anything other than what you absolutely need to survive is allowed. Why? The IRS figures that, if you owe them taxes, you should pay them before you pay your church or engage in costly recreational activities. After all, your neighbors may have scrimped to pay their taxes on time; why shouldn’t you? While the qualification formula is relatively objective, the computations of net equity in assets and monthly disposable income are typically more subjective. Once the ability to pay amount is determined by the IRS (and there’s little room for haggling in this process), the computation results are clear: either you cannot pay the taxes owed and qualify for an OIC, or the IRS determines you can pay the taxes owed and you don’t qualify. However, even if you do qualify for an OIC, many applicants cannot afford to pay the monthly amount the IRS ultimately determines (usually because the IRS has allowed far less for living expenses than you actually spend, meaning they are demanding a higher monthly payment than you can afford).

The IRS and FTB are particularly strict about living-expense budgets when considering an OIC. They want the taxpayer to be made uncomfortable in exchange for writing off some tax debt entirely. On the other hand, they generally allow a higher standard of living on Installment Agreements, likely because that taxpayer is not trying to get rid of debt, simply time to pay it off. This is one of many reasons Installment Agreements are often the best way for clients to pay off tax debt.

Additional Requirements for Offer-in-Compromise Acceptance

There are additional requirements before an OIC is accepted: (1) the taxpayer needs to have filed tax returns for the prior six years; (2) the taxpayer must have had the proper amount of tax withheld or estimated tax payments made for the current tax year; and (3) the taxpayer must begin making estimated payments with the filing of the application, even if it has not been officially accepted. Indeed, it can and often does take two years for the IRS to make a determination on an application; by law, the IRS must reply within two years.

When Does An Offer-in-Compromise Make Sense?

There are times when it makes sense to file for an OIC. If someone owes a tax that cannot eventually be discharged in bankruptcy, I would consider an OIC. What are those taxes?

- Taxes where the taxpayer never filed the tax return, so the IRS or FTB did it for her. The general idea is that if the taxpayer couldn’t be bothered to file their tax return, then Congress will not allow a later bankruptcy to rescue her from her own failure.

- Payroll taxes withheld from employee paychecks by a business owner. Congress treats this as an almost criminal matter: the employer is stealing not only from the government, but from its employees as well, since it was the employee’s wages that were supposed to be forwarded to Social Security and Medicaid. To the extent that the IRS proves a person is personally responsible for this theft, the responsible person cannot get a free pass by declaring bankruptcy and moving on.

- A tax debt incurred by fraud. If I knowingly cheat on my taxes and the IRS can prove it, I’m in a world of trouble. My tax debt is going to be increased by the amount I understated plus a 75 percent penalty. I am unlikely to go to jail, but that’s always a possibility. Congress does not allow me an easy out by discharging the taxes and penalty in bankruptcy.

These scenarios reflect people with greater tax stigma than the run-of-the-mill delinquent taxpayer. The tax authorities will be skeptical about allowing them to walk away from their tax liability. But if the taxpayer can prove current compliance with the law, and that the IRS will collect more from the offer than it could get using its full range of collection efforts, he or she may succeed in obtaining relief from a huge tax debt.

OICs are complex and difficult to get accepted

I don’t do many of these because it’s usually a waste of the client’s time and money. Occasionally, however, the circumstances are right for an OIC. As with so many aspects of tax, it’s best if you speak to an experienced professional first. Let’s discuss the particulars of your tax issue, so that we can fully evaluate all the alternatives available to you with an eye toward your situation. And, even if an OIC is right for you and you’d prefer to do most of it yourself, it’s still good to have someone take a look at it before filing. Call me.