Tax Audits

Audit Triggers

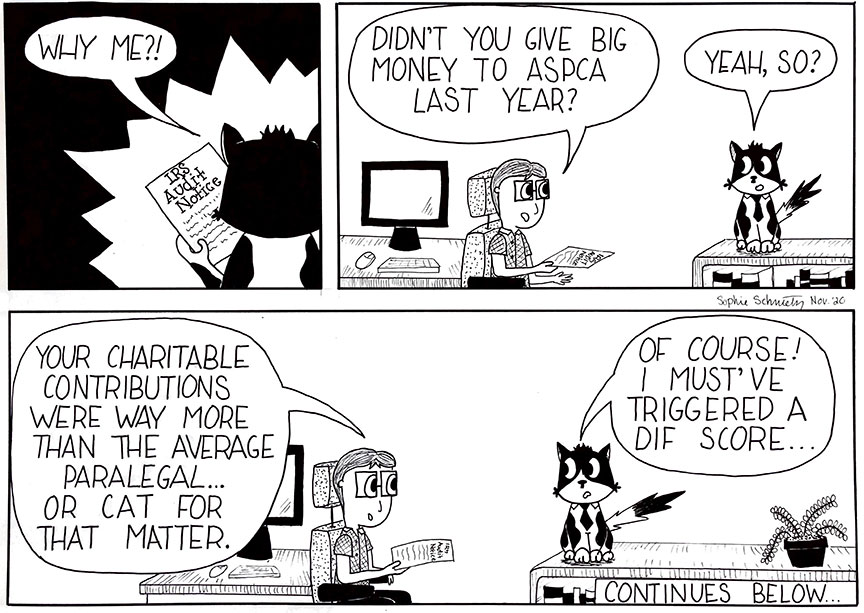

There are several ways the IRS selects tax returns for audit. The infrequent triggers are (1) anonymous tips, which rarely lead to an audit without independent verification; (2) agent-driven audits, where an agent may, for example, see a lower-middle-class neighbor driving a luxury car and investigate, but these also occur rarely because of already-heavy IRS agent caseloads; and (3) a random audit by the IRS’ National Research Program to collect data that finds new patterns of compliance and noncompliance (only 14,000 tax returns chosen annually). By far the most common trigger is a DIF score, in which IRS computers flag returns that have income, deductions or expenses outside their “differential functions.” These DIF scores are averages for particular businesses, professions, incomes and zip codes. If some element of a tax return falls far outside these DIF scores, then it will flag that return for an audit. Some tax return patterns are fairly well-known for triggering the computers’ vigilance: home office deductions, failure to report enough income to match Forms 1099 and W-2, and losses on Schedule C for more than a year or two.

A taxpayer rarely knows or finds out what triggered their audit. More importantly, the reason a taxpayer is selected does not matter. If you’re audited and owe more tax, your defense cannot be “I shouldn’t have been audited in the first place.” A long line of cases, starting with Greenberg’s Express v. Commissioner, 62 T.C. 324 (1974), says the Tax Court cannot question the basis of the IRS’s determination. The legal burden is on the taxpayer to prove the tax return is correct. Challenging the IRS’s right to audit is a waste of time and money.

IRS Assessment Division and Audit Notification

The IRS contacts you initially only via written correspondence sent by US mail. If you receive an email or a phone call from an IRS “agent” you haven’t dealt with before, it’s fake. An audit notice will arrive from one of the IRS Assessment division’s four units. The Large Business & International unit audits firms with assets over $10 million or with international sales or divisions. The Tax-Exempt unit audits non-profit and governmental entities. I do little work in these two areas. Instead, I primarily represent clients being audited either by the Wage & Investments unit, or the Small Business & Self-Employed unit (when I was at the IRS, I worked in this unit).

The IRS Never Calls or Sends Email First

The Wage & Investments unit focuses on individuals whose income is primarily from wages or investment dividends and interest. The Small Business & Self-Employed unit focuses on businesses with assets under $10 million filing corporate or partnership returns, and on self-employed or small business owners filing a Schedule C, E or F with their Form 1040. The IRS divides taxpayers in this way primarily to ensure that its auditors have the expertise to fully analyze the tax returns and financials of the taxpayer group they work with. After all, the skills necessary for an agent to scrutinize the expenses of a small business owner with $100,000 in annual revenues is very different from the skills necessary to scrutinize a multinational firm like Amazon.

Wage-Earner Audits

If you’re selected for audit, you’ll receive a letter from the IRS. Most audits of wage-earning individuals are conducted entirely by mail; the taxpayer and the IRS agent never meet in person or even speak on the phone. These audits typically consist of the IRS asking for specific documentation to verify information on an annual Form 1040 tax return – for example, the closing statement for the sale of a house, the hospital receipts to substantiate a medical deduction, the cancelled check for property taxes. If the taxpayer’s documentation substantiates what’s claimed on the tax return, then the audit is quickly closed. Most individuals can easily submit the requested paperwork and navigate the process on their own. However, if you feel uncomfortable doing so, or the IRS agent makes a request that makes you nervous, call an experienced tax attorney. I deal with the IRS all the time and can give you a quick and accurate assessment of what’s going on.

While the audit process is alien to most taxpayers,

it’s entirely routine to me.

Call me if an IRS request concerns you.

The initial letter from the IRS less frequently asks a wage-earning taxpayer to attend an appointment at an IRS office. If you cannot make a suggested appointment, then you can call and request a different time; your auditor will accommodate requests for schedule changes within reason (ones that appear legitimate, rather than attempts to delay or inconvenience the IRS). Some agents think it’s more efficient to meet in person, while some prefer phone calls. Don’t read any “deeper meaning” into whether you’re asked to respond to an auditor by mail, phone or in person, because there is none. IRS agents have varying preferences for how best to carry out their responsibilities. Very few individuals need to take on the expense of having an attorney with them at their audit; I mostly see individuals after the initial audit is completed, they are unhappy with the IRS’s determination and they want to appeal their auditor’s decision. Click here for more information on the Litigation process.

Audit Timetable: Three-Year Assessment Rule

The IRS has three years from the time your return was filed to assess more tax on it. As a result, the IRS usually wants to complete an audit six months before the deadline date. Some uncommon exceptions allow the IRS more than three years to assess additional tax. First, if the IRS can show that the taxpayer underreported gross income by more than 25 percent, then it has six years to assess more tax (see I.R.C. § 6501(e)(1)(A). However, these are rare cases because the IRS generally has the burden of showing receipt of income. Second, if the IRS can show your return is fraudulent, then it can assess more tax at any time because there is no statute of limitations on a fraudulent return. However, the IRS will have the burden of showing fraud – both that there was an understatement of income, and that the understatement resulted from the taxpayer’s intention to avoid tax known to be owed. The IRS is conservative in its litigation positions, so it rarely raises fraud even when it should.

The actual filing date of a return is not always the obvious one. At first glance, it seems obvious that three years begins from the date the taxpayer filed the return. Let’s take a tax return for the 2019 tax year. If you filed it before April 15, 2019, the law says that the return was filed on April 15. If you had an extension until October 15 and filed the return on September 1, the limitation period starts on October 15. If you filed the return late, the law says that it was filed on the day the IRS received it. Obviously, the law strongly favors the IRS: Congress wants to ensure that taxpayers do not get out of their legal obligation to pay taxes with skillful procedural moves.

Self-Employed and Small Business Audit Notification

These audits generally begin with a letter asking the taxpayer to call the IRS agent assigned to their audit, to set up a meeting. Many agents will request a meeting in the taxpayer’s business location. Small business audits are rarely conducted entirely by mail, unlike those of individual wage-earners, because the complexity of income and expense calculations is greater and thus the IRS agent almost always needs to speak with the business owner to understand how the figures on the tax return were calculated. Most self-employed and small business owners can respond to the auditor on their own. But, if you’re concerned about something, it’s always a good idea to call an experienced tax attorney to ensure your concern isn’t something serious.

Ignoring IRS Audit Letters

After receiving the initial letter from the IRS notifying you of an audit, if you don’t show up or don’t schedule another time to meet with your auditor, then the auditor will make a few more attempts to reach you. After two or three missed meetings or unsuccessful attempts to reach you by mail or phone, the auditor will close the case with a status of unagreed. If you don’t defend or substantiate the issues the audit raised, then the auditor assumes the IRS challenge to your tax return is correct and you will owe the greatest amount of tax possible to assess. The implication? Avoiding the IRS is never good strategy. I have met many people who question the legitimate authority of the IRS and the US government to tax them. Whether you like it, or agree with it or not, yes, the IRS has this legal authority to tax and penalize you. Some clients don’t believe me until the IRS has levied on their bank accounts.

Avoiding the IRS isn’t effective political protest,

or a good way to lower taxes

Similarly, some clients don’t like conflict, or are so disorganized that they simply don’t pay attention to an audit letter. The IRS is not going away just because you can’t deal. In fact, the longer you avoid engaging with the IRS, the more penalties are likely to accrue on your account and the harder it will be to resolve the tax issue. Avoidance strategies keep lawyers employed, but almost everyone will pay attorneys and the IRS less if they respond to audit requests immediately. So, please, do yourself a favor: get organized by filing your returns on time (or an extension), keeping good records on all expenses and deductions and, if you’re audited, responding promptly to the IRS agent assigned to you.

IRS Agents

The IRS Revenue Agent, or auditor, is a federal employee with civil service protection. Agents typically have a college degree and accounting training. There’s wide variety in talent and ambition among the auditors: some pride themselves on their interactions with taxpayers, others on their accounting acumen. Some seem not to pride themselves on anything except showing up and leaving the office at the beginning and end of their workday. Agents are governed by many rules and customs; the general procedures for audits are publicly available in the Internal Revenue Manual. Agents have great discretion in some areas (whether to expand a single-year audit into additional tax years) and very little discretion in others (waiving or negotiating down interest charges). This has all been written into law by Congress.

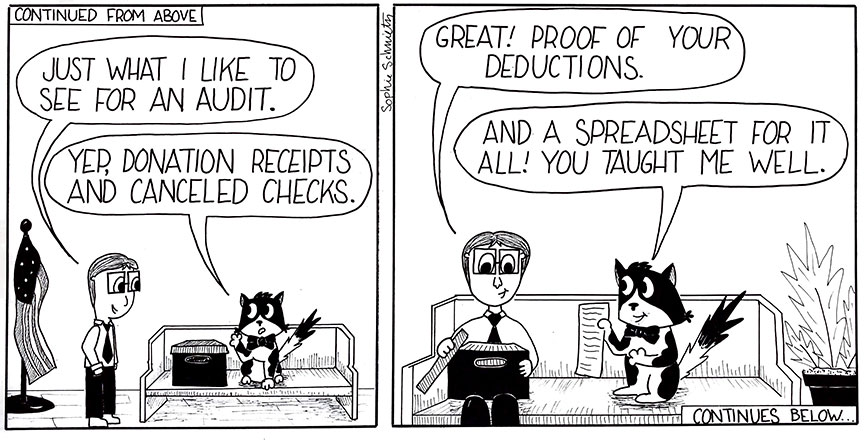

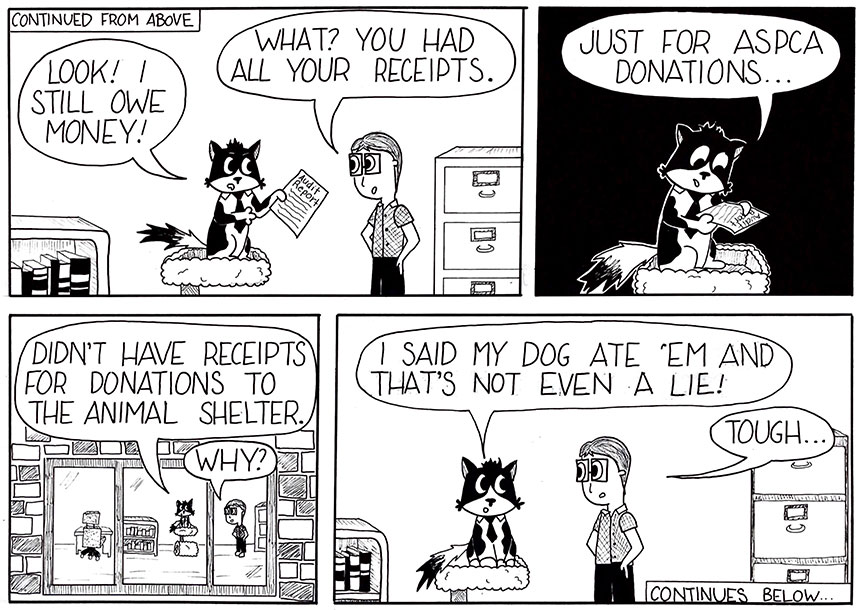

The burden of proof for all information on a tax return falls entirely on the taxpayer. If the IRS agent challenges an expense on your return, you must show proof of payment such as an invoice, receipt, cancelled check or bank statement. If you do not, the IRS agent does not have to allow that deduction, even if you really incurred the expense. Why? The IRS has very little information on taxpayers’ finances other than the wage reports sent by employers, and the investment and mortgage statements sent by financial institutions. Thus, it is the legal obligation of taxpayers to prove what they claim on their tax returns.

Keep all receipts for deductions, expenses and earnings for seven years (in either hard or electronic form – I scan all my receipts), and all receipts and invoices related to capital assets (such as a house or a business investment) for three years after the sale of that asset (in case the IRS audits you or your business and wants proof of the assets’ cost basis and sales price). Keep those files in good shape: the IRS does not need to accept faded, burnt, water-damaged or otherwise illegible receipts or copies of receipts. If you are audited and cannot provide documentation of the expense/deduction, then it’s virtually impossible to get the IRS to accept just your word of honor. Why? You could be lying and that wouldn’t be fair to fellow citizens who pay their full share of taxes and can prove it. More importantly, the IRS is legally obligated to treat all taxpayers as guilty until they substantiate the claims on their tax return. The IRS cannot cut special deals with some taxpayers and just accept their word. Implication? You can cry in front of your auditor or scream at him, but he will still disallow any deductions or expenses for which you don’t have documentation. That’s their job and the law. Tears and anger are not proof of deductions.

IRS Agents must assume the taxpayer is guilty until proven otherwise, so keep all receipts and invoices for 7 years

The Tone of Interaction with Your IRS Auditor Matters – a LOT

When you receive the “invitation” from the IRS to attend an audit meeting, how you respond initially often determines the tone of future interactions with the IRS agent in charge of your audit. This is important because your IRS agent has discretion to make the audit relatively more easy or difficult. In almost all cases, the best strategy is to be cooperative and polite with your IRS agent, even if you and your accountant or attorney believe the audit is frivolous, your IRS agent rude or incompetent, and the entire process a huge waste of time and money. I cannot stress this enough, particularly because so many of my clients are outraged by the audit process.

Many clients typically hate (rightly so) what feels like an invasion of privacy. They don’t like when their honesty is questioned. Some don’t like how Congress spends taxpayer money and don’t want to cooperate with an enterprise they disagree with. Many clients want me to be a pit bull with the IRS agent. They want me to be as outraged as they are. But I’m not. Why? Because it’s a waste of my time and their money. The IRS has the full power of the federal government behind it and every legal right to be invasive and annoying. Very occasionally, when I’ve encountered a particularly incompetent or vindictive agent (which is rare), I have gone to their superiors and agitated for their removal from my client’s case, while still treating the inept agent cordially. It does no good to antagonize the person with the full authority of the federal government to determine the outcome of your case. This is why I am upfront about my “style”. If you need an attorney who’s as pissed off at the IRS as you are and will wage overt war on your behalf, then I’m not your guy. If, on the other hand, you want an attorney who accepts that the better way to deal with this frustrating bureaucracy is to treat IRS agents politely, then I am your guy. Remember: I worked for the IRS for a decade. I know what gets clients the best results because I was on the other side of the desk.

Being obnoxious to an IRS agent, who’s just doing their job,

has never gotten me a better outcome than being cooperative or politely resistant

Presentation of Requested Documentation

When you show up to the initial audit conference, or host the auditor at your business, the auditor will ask first about your background: how much education you have, your work, your business. Then she’ll ask you to provide documentation for the items in your return that are under investigation and which were requested in your audit letter. Your initial audit letter (typically letter 3573) is almost always accompanied by an Information Document Request (Form 4564), as in this example. Your auditor also will provide a deadline for you to supply additional information, if any. She will almost always be flexible in accommodating your schedule, particularly if she believes you are cooperating. Even if you miss one or two of the deadlines that the auditor set for you to provide back-up documentation, the audit is likely to remain open, rather than go into unagreed status.

However, missing deadlines make auditors suspicious; they wonder what you’re hiding or avoiding. And, the more suspicious they are of you, the more incentive they have to dig deeper into your return, or to expand the number of tax years being audited. I cannot stress this often enough: polite cooperation (which is not the same as agreeing with the IRS’s determinations) with your IRS auditor is almost always the best strategy to minimize both the amount of time the audit will take and how much you will ultimately owe in taxes. I’m sure this advice seems ridiculously obvious but many of my nice, rational clients become irrationally angry and vengeful when the IRS starts grilling them about their financial affairs.

You should organize the requested documents to make it as easy as possible for your auditor to understand and go through them. Collect receipts and list them in a spreadsheet. Provide explanations for why particular items are included. For meal receipts, include the names of the participants and the nature of the business conducted. For mileage logs, refer the mileage notations to objective evidence showing that the car actually drove this far (such as repair bills). The more documentation, the better since the IRS agent starts with the assumption that you are entitled to no expense deduction until you can prove you incurred the expense. For example, you can argue it’s impossible to conduct your business without driving at least 10,000 miles a year, and the IRS agent may even agree with you on an abstract level, but unless she sees some objective evidence to support that you actually drove that much, she will allow nothing. Remember: the burden of proof is entirely on the taxpayer to substantiate all deductions.

Make the documents the IRS auditor requests easy to review

IRS Challenges to Income

The burden of proof shifts to the IRS on matters of income: if you don’t agree with its determination, the IRS must prove an income figure different from what you claimed on the tax return in question. The IRS has two primary methods of determining or proving income. First, the IRS compares all third-party payors’ Forms 1099 that have been issued to the taxpayer against the income reported on the taxpayer’s return. If there is a discrepancy, the IRS may issue a statutory notice of deficiency, but it will need to show more evidence than just Forms 1099; it will need further declarations and canceled checks from the third-party payors. Second, the IRS can find unreported income by doing a bank deposits analysis. It takes all of a taxpayer’s bank statements from the audit year, adds up all the bank deposits on those statements, and tries to subtract all the nontaxable deposits (loan proceeds, gifts, transfers between the taxpayer’s accounts). That number is total income; it compares this figure to the income reported on the return. The bank deposits analysis is usually recognized as a valid way for the IRS to prove its case of unreported income. If there is a discrepancy, the IRS may issue a Statutory Notice of Deficiency based on the unreported income.

Unsure whether having an attorney at your audit is necessary?

Call me

Multi-year Audits

The IRS can extend an audit into multiple years if it decides to do so. For example, if there is a problem with the 2019 return, the IRS can expand that audit to the 2020 tax year, examining the same issues. And no court can review that IRS decision because, again, the Tax Court cannot question how the IRS arrived at its audit decision. The only time the IRS cannot continue to expand an audit is when agents have already examined an issue for multiple consecutive years and found no change in tax liability; then, as a matter of policy rather than law, the IRS will not reopen that issue again for several years.

You’re Responsible for Your Tax Return, Even if You Didn’t Prepare It

Let’s say you used an accountant or tax-preparer who claimed fictional deductions that the IRS has exposed in an audit. You were busy and signed your return without looking closely at it. Maybe you were delighted at the unexpected refund. Maybe you’re too busy running your business to want to delve into the business accounting. Since your accountant lied, you’re not responsible for the unpaid taxes and interest, right? Wrong. Taxpayers owe the correct amount of tax, regardless of whether it was reported correctly. They can’t shift their tax responsibility onto the person who prepared the return, no matter how poorly it was prepared, or how little interest a taxpayer takes in looking over the work of a preparer to ensure it is correct. The IRS believes that if you earned the money, then you owe taxes on that – whether it was you who calculated the amount owed, a tax preparer, or the IRS. Every tax return contains the declaration that the taxpayer has “examined this return and accompanying schedules and statements, and to the best of my knowledge and belief, they are true, correct, and complete.” And every tax return must be signed, even if just electronically.

Let’s say a tax preparer’s error was something non-obvious or technical – such as how to report capital gains – and it was the first time a taxpayer was claiming capital gains: if the preparer put them on the wrong line, the IRS would likely not have expected a layperson to have caught this error. After all, it is precisely for such arcane, detailed expertise that most of us hire tax preparers in the first place. I.R.C. § 6664 and associated regulations outline how the negligence penalty can be waived if a professional was used to prepare returns. (And if you clicked on this link and tried to read the nearly unintelligible legal-speak, you no doubt understand why many taxpayers hire an attorney to help them). Broadly, in order to qualify, the taxpayer has to provide all pertinent information to the preparer, the preparer has to be competent, and the taxpayer has to show a good-faith effort to report the proper amount of tax. Even then, you’ll only get out of penalties – not additional tax and interest.

You (or your firm) can’t get out of paying taxes because you used an accountant or tax-preparer, even dishonest ones

IRS Audit Report

At the end of the audit, the IRS agent will issue a report, and send it to the taxpayer. The Audit Report includes brief explanations and the computations of how the IRS arrived at its final determination of taxes, and any penalties and interest owed. Here’s an example of an Audit Report of a wage-earner and here’s an example of an Audit Report for a small business. Notice how many of the expenses the small business claimed that the IRS auditor disallowed because the business owner had no receipts or documentation to verify these expenses. This illustrates the mantra: keep all receipts and invoices because it’s the taxpayer’s burden to prove expenses and deductions! The audit report will also include Consent Form 5564 (see official IRS discussion here, because the government wants to make it easy for the audited taxpayer to agree with its findings. If the taxpayer agrees with the findings and signs Consent Form 5564, then the audit process stops, the IRS assesses the amount owed, and the account goes to the IRS Collections division. The taxpayer’s next correspondence from the IRS will be a bill, and s/he can no longer challenge the amount owed.

If you disagree with the auditor’s findings, it’s worth it to call the auditor to go over the findings, or to ask to speak to the auditor’s manager. However, the auditor is rarely able to change their report because s/he has little discretion to do so; the auditor’s Group Manager can and does sometimes make changes. Read more about Group Managers here.

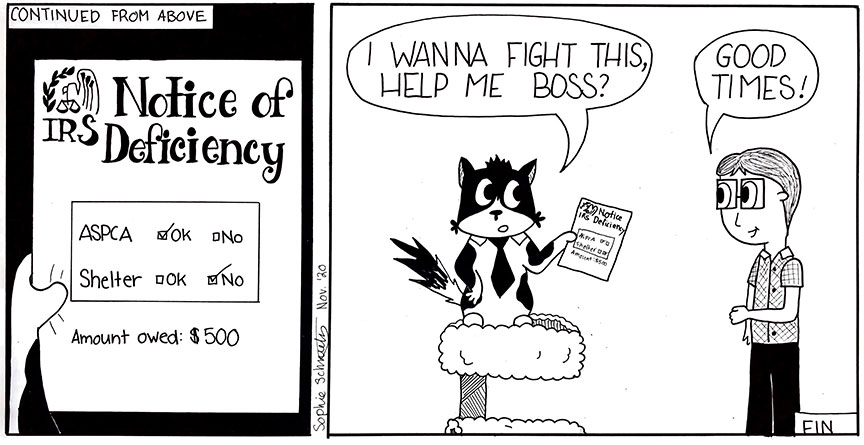

Statutory Notice of Deficiency

If a taxpayer disagrees with the audit result, and refuses to sign the Consent Form 5564, then the IRS will send a Statutory Notice of Deficiency. It can take anywhere from two weeks to six months for the IRS to issue this letter, depending on how backed up they are. The Statutory Notice of Deficiency tells the taxpayer that the IRS is done talking, the taxpayer owes the amount shown in the Audit Report and, if the taxpayer doesn’t like this result, s/he can sue the IRS. Until the Statutory Notice of Deficiency is issued, the IRS auditor is just proposing a change to your tax return. Once the Statutory Notice of Deficiency is issued, the IRS has made the auditor’s position formal and legal. The statutory notice expresses the determination as a “deficiency,” that is, the difference between what was shown owing in taxes on the tax return you filed, and what the tax return should have shown, according to the IRS. In addition to the difference in tax owed, the Notice of Statutory Deficiency details all penalties owed including failure-to-pay, failure-to-file, negligence, or fraud as the Notices in the links above illustrate.

Here’s an example of a Statutory Notice of Deficiency for a small business, and for an individual. Additionally, if you never responded to the IRS’s audit requests for documents or meetings, then the agent has no choice but to eventually issue the Statutory Notice of Deficiency against you. If you plan to challenge your audit, then you want the IRS to issue the Statutory Notice of Deficiency because you cannot file a petition against the IRS without the Statutory Notice of Deficiency.

So, while receiving a Statutory Notice of Deficiency is intimidating, your ability to challenge your audit rests on the bureaucratic processes it opens up.

If you have never been audited or worked for the IRS, it can be confusing and frustrating to navigate the audit process. However, many people and business owners do fine responding to IRS audit requests on their own. I usually step in after the taxpayer receives the Statutory Notice of Deficiency which is when the bureaucratic processes become more complex and thus when specialized knowledge can be very useful. However, if you feel uncomfortable at any time during your audit, call me. We’ll figure out whether you just need a bit of quick coaching to deal with the audit on your own, or whether it would be helpful for me to become directly involved in your audit.

Once you’ve received a Notice of Deficiency, the audit is formalized – time to pay or file a petition in Tax Court to sue the IRS

Bad Audit Result? What’s Next?

You can fight the audit result in the Statutory Notice of Deficiency. In the letter with this notice will be the form to file a petition against the IRS in U.S. Tax Court; you can also find all relevant information on the Tax Court’s website here. You have 90 days from the date your Statutory Notice of Deficiency was issued, to file this petition. Do it. Do it immediately. Even if you don’t think you want to go all the way to trial (a long and often costly process), filing the petition opens up negotiation avenues with Appeals officers and IRS attorneys, both of whom have much more power and discretion to adjust the auditor’s determination. This is also the best time to consult an experienced tax attorney – either to coach you through the process to prevent costly mistakes, or to step into the process on your behalf if you don’t have the time or energy to do so yourself.