A client called me with a strange problem. He and his brother had inherited real property in Nevada. Because the brother was less than fully-functional, the client held his brother’s share as trustee in a spendthrift trust. And to protect themselves, they held the property in a limited partnership; the client had created a limited liability corporation to manage the limited partnership, and the client was the manager of the limited liability corporation.

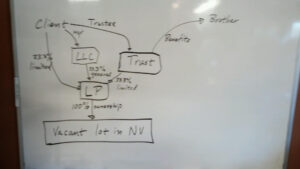

All these levels of corporate protection work just fine. Here’s how it looked when the client called me (I love my whiteboard. I couldn’t do half the stuff I do without putting it up so I can see it).:

But the client wanted to purchase new property, using I.R.C. § 1031 to make a gain-free exchange. The new lender wanted to see the tax returns of everyone involved in this scheme, including the brother’s tax return. Because the brother had horrible credit, this would mean that the client would be paying very high interest rates for the loan on the new property. The client wanted to create a transaction to remove the trust from ownership of the real estate and the limited partnership, because he couldn’t get a decent loan.

This floored me. The point of a spendthrift trust is to legally insulate the trust’s beneficiary from the consequences of the beneficiary’s actions. Theoretically, the beneficiary, the ne’er-do-well brother, could light cigars for his lap dancer with $20 bills, and it should not affect the creditworthiness of the trust. And the trust was only a limited partner – a lender cannot reach it to satisfy a judgment on a loan to the limited partnership that went bad. The creditworthiness and tax returns of the trust and the beneficiary should be irrelevant to the lender.

I thought my client didn’t have a legal problem, he had a business problem. He just needed to find the correct lender.

Whenever I have a question about lending on real estate, I call my go-to expert, John Cofiell. John confirmed that, because of post-2008 lending regulations, lenders now require the tax returns of every individual who has more than a 25 percent share in real property, including beneficiaries of trusts. No, it doesn’t make sense to him, either, but the government overreacted to the loosey-goosey lending environment of the mid-2000s.

The client wanted to have the trust distribute the limited partnership interest straight to the beneficiary, then have the beneficiary donate it to my client, the trustee. The first transaction was tax-free; the second implicated gift tax. My client would then pay his brother’s living expenses for the rest of his life. Could I document that transaction?

No, I could not, because it would not help the client. The Franchise Tax Board had liens against the brother for unpaid taxes. Chances are that the FTB would never find out about the transaction, but if it did, it would have a claim against the brother for a fraudulent transfer. We wanted to avoid this.

Better, I said, to have the trust transfer the limited partnership interest directly to the client, the trustee. As trustee, he has a fiduciary duty to his brother; if he deems that this transaction is in his brother’s interest, it is within his power to do it. No one but his brother would have a claim against my client. Because the brothers had a good relationship, they could sign an agreement that the trustee would hold the brother’s share in his own name. This would protect the trustee against the brother’s heirs.

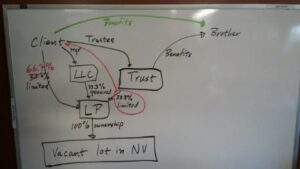

Here is what the final transaction looked like:

The client and brother went away happy. The FTB and the brother’s other creditors, not so much. But the family lives on, preserving its wealth.

This was a situation like a puzzle. And I love a good puzzle.

August 29, 2015