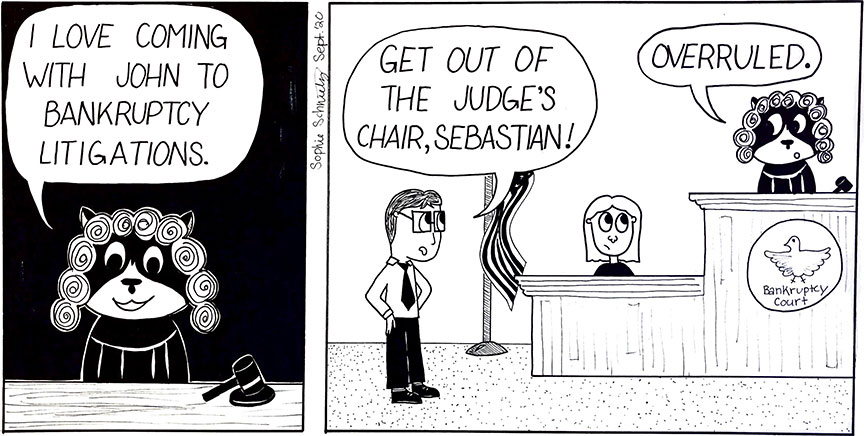

Bankruptcy Litigation

Bankruptcy is a legal process that ends in a discharge, a piece of paper that says that the debtor no longer owes the debts incurred prior to the case. Sometimes cases have facts that take them outside the standard processes of administering the program of generating discharges. Sometimes creditors can’t or won’t accept that the debtor is walking away with a discharge of the debt.

Challenging A Bankruptcy Discharge of Debts

Fraud. The most common reason for creditors to challenge the discharge occur in cases of fraud. If I convince you to give me $200,000 to invest into real estate, promising you that the money is going straight into purchasing a vacant lot where we can build a new housing development, but I use the money to live in a suite at the Bellagio for a week and play the slot machines, that’s fraud. Congress has decided that I can’t walk away from that debt in bankruptcy.

Malicious Tort. Similarly, if I get involved in a bar fight and punch someone, I’ll probably answer to the victim in a court case (I may also answer to the sheriff, but I’ll ignore that here). That’s a malicious tort. The victim will get a judgment for a personal injury, and Congress has decided that it would be unjust for me to be able to walk away from that debt. I may file bankruptcy but I still have to pay the guy I slugged in the bar (for what it’s worth, I actually do not get into bar brawls regularly. Or ever).

Looting a Business From a Position of Trust

If I work as a bookkeeper but stole some of my bosses’ funds for my own gain, that’s embezzlement. Similarly, if I go into partnership with my college roommate, earn a lot of money for the partnership, then take the money and skip town, that’s “defalcation” (a fancy word for stealing). I can’t discharge this debt.

Adversary Proceeding. These cases are exceptions to the general rule: if I file bankruptcy, my debts are discharged. And these exceptions are a sufficiently big deal that a creditor must file a separate lawsuit (an “adversary proceeding”) as a part of the overall bankruptcy proceeding. That lawsuit involves all the pomp and ceremony that one expects in a lawsuit: it is, literally, a federal case. The creditor must file a complaint, have the court issue a summons, serve the summons on the debtor-defendant, and provide certain disclosures to the debtor-defendant. The defendant then needs to answer the complaint. Next, the parties engage in discovery (depositions, requests for admission, requests for documents). Sometimes one party or the other can win by filing motions: a motion saying that the complaint does not state a genuine cause of action, or a motion for summary judgment saying that a trial would be a waste of time because the undisputed facts compel a particular outcome. Because these cases involve exceptions to the general rule of dischargeability, courts look narrowly at whether a particular debt fits the exception or not.

I enjoy the intellectual puzzle and fight of showing that a particular debt does or does not fit the exception. Many attorneys do not understand the elements of a fraud claim or a malicious tort (to be fair, these elements can be complicated and not easy to master). But I do. If you are a creditor in a bankruptcy, call me to discuss whether there is a way to challenge the discharge of your debt.

Back to the adversary proceeding: If neither party wins by filing motions alone, then the case goes to trial. Here, a good attorney needs to know both the elements of the cause of action (malicious tort, fraud, etc.) and rules of evidence. For example, one needs to recognize hearsay in the middle of an opponent’s testimony to stand up to object to the testimony. I have been trained by some of the best attorney schools in the country (National Institute of Trial Attorneys, the Internal Revenue Service, and the U.S. Department of Justice), and I love cross-examination of a hostile witness.

Costs. In general, adversary proceedings are costly because they typically require a great deal of time, as do most trials. As a result, I often advise clients not to pursue an adversary proceeding not because the matter lacks merit but because it doesn’t make financial sense. Conversely, challenges are sometimes worth it – even for a strapped debtor coming straight out of bankruptcy. Collectability and practicality in these cases is key. For example, is it worth it to get a $200,000 non-dischargeable judgment against someone who has lost it all? Does it make sense to spend $10,000 to defend a case where the creditor is trying to claim that $20,000 shouldn’t be discharged? Since the facts of each case are different, the practicality of pursuing an adversary proceeding varies enormously. I will always give you my best assessment of your chance of prevailing, as well as my opinion on whether it makes economic sense.